ALI BANISADR. BEAUTIFUL LIES (CLICK HERE)

30.04.2021 - 29.08.2021

ON THE OCCASION OF DANTE’S 700TH DEATH ANNIVERSARY, THE MUSEO NOVECENTO PAYS TRIBUTE TO THE SUPREME POET WITH THE EXHIBITION ‘BEAUTIFUL LIES’ BY ALI BANISADR, HOSTED BY THE MUSEO OF PALAZZO VECCHIO (SALA DEI GIGLI) AND THE MUSEO STEFANO BARDINI.

The Museo Novecento leaves its home in Piazza Santa Maria Novella and, as on previous occasions, offers a new encounter with contemporary art at Palazzo Vecchio, Sala dei Gigli, and at the Stefano Bardini Museum. From 30th April to 29th August 2021, both venues will hold the exhibition BEAUTIFUL LIES by Ali Banisadr (Tehran 1976), curated by Sergio Risaliti and organized by MUS.E. After leaving Iran with his family, at the age of twelve, Banisadr reached first Turkey and then the United States, stopping over first in San Diego, then San Francisco, and ultimately settling in New York, where the artist still lives today.

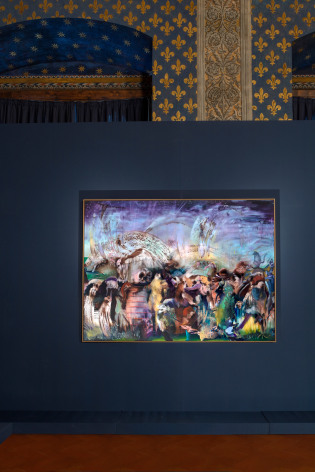

This exhibition, the artist’s first in an Italian state museum and in Florence, instigates a dialogue between his work and Florence’s history. At the Bardini Museum, famous for its deep blue walls, known as Bardini ‘blue’, the artist’s paintings will be shown alongside the collection of Stefano Bardini, its medieval and Renaissance marbles and paintings, its Persian rugs and shining armour. In Palazzo Vecchio, Banisadr has been commissioned to create a group of site-specific paintings inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy, a special event organised by the director of the Museo Novecento, Sergio Risaliti, as part of the celebrations commemorating the 700 year anniversary of the death of the Great Poet.

Born in Tehran, Ali Banisadr moved to the United States with his parents when still a child, after having lived through the Iran-Iraq war. His first drawings were done in his basement, while the city was being bombarded. Aged twenty, Ali Banisadr reached San Francisco where he came into contact with the Mission School’s art movement. He then moved to New York in 2000, to study at the School of Visual Arts. In 2006, while at graduate school at the New York Academy of Arts, he won a scholarship to travel to Normandy. Visiting the D-Day beaches, Banisadr experienced a kind of “hallucination”. He says he was certain of being in the midst of those past events, reliving the landing physically, “being able to hear the whistling and banging, feeling everything within my body as if it were real”. This experience was for him a true initiation and revelation. When back in New York, he started a series of charcoal drawings, ”more real than anything done before, more free and instantaneous”, all based on the sound of explosions – similar, in this respect, to the drawings done in his childhood. “This was a revelation for me, because I was really feeling these drawings in my body”– said the artist –”I knew that this experience was too important not to be carried forward.”

In this sense, his work exemplifies a process of multisensorial simultaneity, a typical example of synesthesia, which takes place when two different sensory experiences coexist. His paintings simultaneously combine visual memory, sounds, impressions, collective memories, imagination and other data orchestrated within the same pictorial frame. “I can paint something starting from a memory, from an internal vibration which still lives deep inside me, or is generated by a sound I heard when I was a child…The crater painted during that trip to the beach appeared so suddenly that it connected immediately to my first memory of hearing bomb explosions and seeing craters in the ground. I remember that it all came pouring out so quickly that I used everything there was around, rags, spatulas, twigs or anything else, just to be able to transmit that sensation I was feeling of a past memory”.

This synesthetic connection between auditory and visual memory is coherent throughout his oeuvre and determines its formal construction. If the imaginary world he represents is very personal, the way it is formalised instead constantly refers to the history of art. When standing in front of his work, iconographic sources can be found, from Hieronymus Bosch and Francisco Goya, but also Max Ernst and Willem de Kooning, combined with references to Persian and Ancient Near Eastern art. Banisadr is also drawn to North-European landscape painting that vividly captures the effects of light and atmosphere: “As a rule, I have always been interested in historical Renaissance paintings, because they are more allegorical, mythological, and do not refer to a particular time and place”.

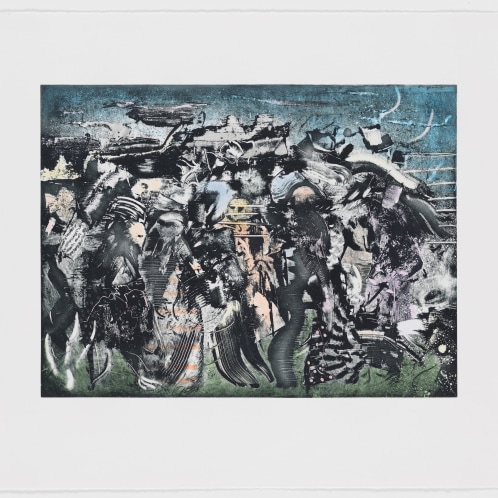

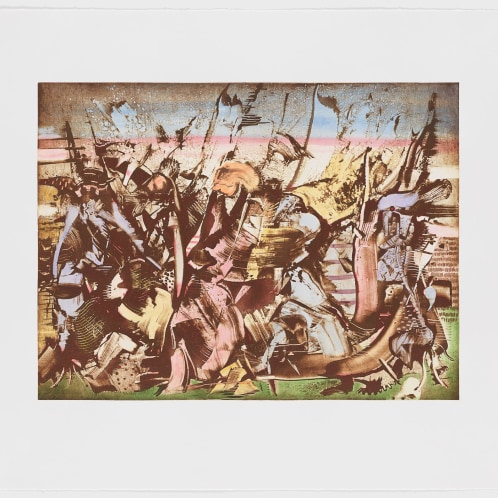

Banisadr’s paintings are inhabited by a surreal cast of characters, seemingly appearing and disappearing, as if raked and swept over by a storm and dragged into an apocalyptic chaos. It is a pandemonium, albeit an orderly one, even if every creature does not correspond to an identifiable character. Everything is in motion, the different areas of his painting move at different speeds; here the characters stand still, now they are restless, buzzing with energy. There is something fascinating and puzzling, which denies any objective description, and the subject seems both evanescent and mysterious, arousing wonder. These compositions are like a symphony with high pitch, dissonant notes finding an equilibrium thanks to a subtle organisation of depth planes, colour tones and temperature and that synesthetic attention with which points of strength are distributed across the canvas, without a main focus or a privileged point of view.

As in a bird’s flight, the view is taken from above and one’s gaze never concentrates on a single focal point, a single action, a prominent character, while almost confounded by the variety of anthropomorphic or naturalistic detail, as in a carousel, when the whole world spins and starts losing focus as a result of speed. Hierarchy disappears. Banisadr does not use geometric perspective to line up the elements in order of importance. Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner and Willem de Kooning, as well as Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the elder come to mind, because somehow, and with all due iconographic differences, we also do not recognise a centre in their paintings; “their composition is called ‘all over’ for this reason, because every part of the painting, every character included, every animal, tree, anything – all are equally important.” – the artist explains – “There is no hierarchy. I find all this very interesting. Because one’s eyes can move within the painting, and there is no way of finding a hierarchical character. All are equal, all share this energy within the painting”.

Chromatic subtleties lead our gaze through a cosmogony, from one scene to the next, and then into a microcosm enlivened by countless details; it is as if the carousel slowed down and our eyes fell on mysterious revelations, and surreal and otherworldly beings. In the whirlwind of his paintings, Banisadr stages a world that draws from the past but also from the present by evoking the speed and simultaneity of the internet.

This idea of embedded worlds is one of the main reasons for Banisadr’s fascination with Dante. The Comedy also contains a whole world in its verses: Alighieri, – according to Banisadr, a passionate reader of the Comedy – included characters from mythology and epic poems, historical characters and his political contemporaries. Inferno (Hell) is, sometimes, that place where apocalyptic scenarios become reality. A synthetic poem, a pandemonium which has inspired Banisadr’s paintings made especially for the exhibition as suggested by their titles SOS, Underworld and Beautiful Lies and their flame-like brushwork and choice of palette.

“I think that collective memory is something very deep inside ourselves” continues the artist “It is something in the public domain, which we can all access. I am sure that Dante too drew from this source and I like the way the narrative develops, bringing the protagonists further and further deep into the earth. I find that this is a metaphor for a personal journey deep within ourselves, to discover what is hidden inside us. This is the place, intimate and profound, where I always go to find symbols to express myself in my paintings”.

Beautiful Lies, one of the works inspired by Dante exhibited in the Sala dei Gigli in Palazzo Vecchio with SOS and Underworld, and to be hung opposite Donatello’s Giuditta e Oloferne, has been chosen to give its title to the exhibition. The expression “beautiful lie”, under which truth hides, is used by Alighieri himself to speak of his work and allegorical poems in general, and perfectly befits Banisadr’s work, with its energetic brushwork and its chromias ranging from psychedelic to monochrome; it displays his inner world (and the universal one), made up of violence and isolation, anxiety and wonder, but also memory and imagination.

ALI BANISADR

Beautiful Lies

30th April – 29th August 2021

Museo Stefano Bardini, via dei Renai 37 (Ponte alle Grazie)

Opening times: Monday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday 11.00am – 5.00pm

(last entry: 4.00pm)

Museo di Palazzo Vecchio, Sala dei Gigli, Piazza della Signoria

Opening times: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday: 9.00am – 7.00pm; Thursday: 9.00am – 2.00pm.

The exhibition ticket is included at the entrance to the respective museums

Enquiries

Museo Novecento

Piazza Santa Maria Novella 10, Florence

Email: info@muse.comune.fi.it | segreteria.museonovecento@muse.comune.fi.it

www.museonovecento.it